Saïs Report, 2010

Season Reports

Saïs Report, 2010

Introduction

This year the Sais project continued to study pottery from the waste-water project in the village of Sa el-Hagar, as well as surveying and drill augering in neighbouring villages, in order to to add to information about the places which would have been closest to Sais in antiquity.

Preliminary report on the season in Arabic.

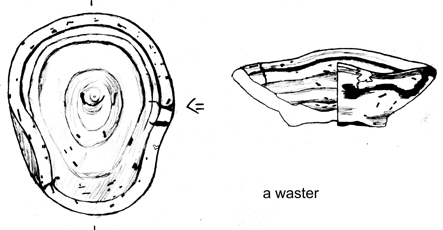

A waster bowl.

Surveying in Surad under the watchful eye of a gemusa.

We also began a small project called the ‘Saite Kilns Project’. Based on previous work in the village of Sa el Hagar, specifically on the western side of the ‘Great Pit’, it is likely that this area was the more industrial area of the city from the Saite period through to the Roman period. There may have been pottery and faience kilns in this area, so we intended to find evidence for kilns and manufacturing processes during the Late Period, from actual objects made in the kilns, if not the areas of the kilns themselves. The work was ambitious, not least because this part of the site is basically the track on the western side of the Great Pit, bordered by modern housing and disturbed by water pipe and telephone cable trenches. Funding and other support for this project was provided by the Wainwright Fund of Oxford University, the British Academy Small Grants Fund, Cath and John Rutherford, Muriel Wilson, Exotic Tours and the North East Ancient Egypt Society. We gratefully acknowledge all of their help, as well as the continuing sponsorship of the Egypt Exploration Society and Durham University.

Excavation 11 in the heart of Sa el Hagar, with the local Kiddie Kart passing by, taking children to school.

In addition, there was time to continue post-excavation work preparing the Prehistoric material for excavation. Dr Karl Lorenz, a scholar with a Fulbright Scholarship from the USA was interested in the Buto-Maadi period material we had excavated in 2005 and he had been visiting other excavations and projects with material from a similar date. His brief visit to Sais enabled us to examine carefully some of the polished sherds we had found, with some interesting conclusions, which can be found below.

This work will be included in The Prehistoric Period at Sais (Sa el-Hagar): Final Excavation Report .

‘Fibrous’ Predynastic Lower Egyptian pottery sherd.

Mikaël Pesenti from Aix-en-Provence University was also part of the team and is working on Archaic Greek Amphorae from Egypt for his Doctorate. He has been working with the material from our Saite Period Excavation 4, which will be the next volume in the Sais Excavation series after Sais 1 : Ramesside Period at Kom Rebwa and Sais 2 : Prehistoric Sais.

Mikäel Pesenti trying to light a match with a magnifying glass – an important skill!

Overall, this year, the results of the work gave us excellent information about the way in which the city of Sais had developed from the Late Period and of the type of finewares, which may have been locally produced and distributed from the Late Ptolemaic to Imperial Roman period. We also made good progress in our research and studies, working towards those excavation publications.

Topographic survey, drill augering and pottery study in the environs of Sa el-Hagar.

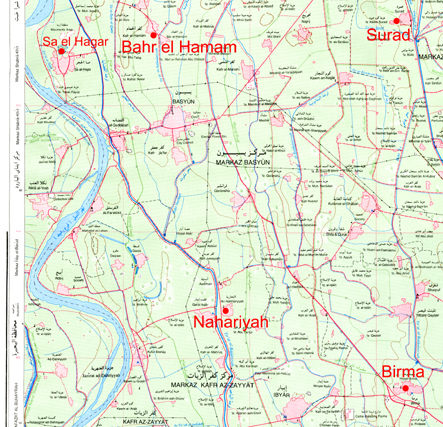

One of our questions about Sais was about the satellite towns that once my have supported and served the main city. The survey work in nearby towns and villages aims to identify ancient sites underneath modern villages or in areas that are no longer inhabited. In 2010, we chose 4 towns to visit and to survey and drill auger, in order to discover as much as possible about their ancient past.

Map showing the location of Sa el Hagar (Sais) in relation to Bahr el Hamam, Kom Surad, Nahariya and Birma.

Ezbet Kom Surad: N30º 58.634’ E030º 54.303’

The area adjacent to Ezbet Kom Surad was mapped and a pottery survey was carried out in the fields around the Ezbet and between the Ezbet and the cemetery on the eastern side of Surad. Three drill augers were carried out: one the east side of the Ezbet, the second inside the Ezbet and the third in the fields to the west of the Ezbet.

The area was selected as having archaeological interest because of the pottery lying in the fields, which was noted last year and because of the section at the west side of the Ezbet, bordering the fields which contained a good cover of pottery. The survey suggested that the pottery cover extended to the north of the cemetery area and Ezbet and to the south, as well as the east of the Ezbet. It was difficult to discover whether this material had been spread on the fields in earth from elsewhere or whether it came from a small kom-settlement which had been removed and only remained under the Ezbet and the cemetery.

Heba abd el Gawad from Durham University and Fatima Rageb of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, gamely wandered through potato fields, dodged dogs and enlisted the assistance of local children and Tuk-tuk drivers in carrying out the survey work.

Heba abd el Gawad in the fields.

We also carried out a sherd density survey, where 1m circles were made in the area and the total number of sherds in each was counted in order to show where there were dense concentrations. The results suggested that there was a higher density of sherds towards the south and east, with a comparative fall-off on the north. Nine fields were field-walked and diagnostic sherds were collected from them. Amongst the diagnostics identified in the preliminary study were a handle from a Gaza amphora (4-6th century AD), casserole handles (4th century AD onwards), massive pie-crust rims (4th-9th century), ribbed amphora body sherds (Late Roman) and one fragment of a base of a CpRSW bowl with embossed decoration (6th century onwards). This material suggested a date for the pottery scatter of the Late Roman period, although there was one painted sherd which is probably later 9th-10th century and there was also modern pottery and rubbish in the fields.

One of Fatima’s field survey pottery selections.

The drill auger suggested that there were relatively unoccupied areas of alluvial lands on the east of the Surad area. The Ezbet itself had about 4.5 m of settlement deposits including pottery sherds, charcoal and distinctive loose earth fill. It seemed to be founded upon a thin layer of tafl-clay which was hard to account for in the centre of the Delta. Under one of the fields where pottery was collected, the drill auger again suggested that this was an area of rich alluvial silt. In conclusion, the Ezbet sits upon the remains of a small settlement mound from which some parts of its edges may have been removed. The pottery suggests that its main period of occupation was in the Late Roman period.

No survey work was carried out in the town of Surad itself, but this could be an interesting comparison for future work.

View north between Ezbet Kom Surad and the cemetery of Surad, showing area where the old kom may once have stood.

Appendix 1 : List of areas surveyed

Bahr el Hamam N30.9719º, E030.80761º

Cemetery mound covered in Roman Period pottery.

Previous drill augers in Bahr el Hamam in 2006 suggested that there was a sand hill to the west of the Salamuniyah Canal and it was further investigated to see if there was any evidence of occupation of this sand area.

Three drill augers were carried out to the west of the canal, just to the east near the tomb of Sidi Ali Maghrabi and then further east, south of the cemetery, which was a mound covered in Late Roman pottery. The augers confirmed that, although there was sand on the east of the canal as well as on the west, it is most likely to be part of a river system rather than a gezira. The sand was fine and this meant that it was difficult to obtain samples from deep down, so it was not possible to be certain from where the sand originated. The east and the western sides did, however, show that there was extremely compact alluvial deposits on either side of the sand, which may have been levee banks. The modern canal seems to occupy an older river distributary bank, but it was noticed that there were many sherds lying in fields between the eastern drill auger and the canal and that the cemetery seemed to be built upon a mound composed of Late Roman sherd material. Diagnostics sherds were collected for study. Some granite stones and a quartzite block were also observed in the village, which may have been brought here from Sa el Hagar.

Further work here would be useful to elaborate upon the earlier settlement at Bahr and Kafr el Hamam.

Area of drill auger 2, with a tomb of a sheikh and corn bins.

Nahariya N30º 52.500’, E030º 50.119’

Area where the mosque of Mohamed ibn Zeid stood and before the new mosque has been built.The mosque of Mohamed Ibn Zeid was demolished in 2007 and many inscribed blocks were removed to the SCA magazine at Tell Farain. The blocks seemed to have originated in Sais and have been known since Labib Habachi published some of them. The survey visit was designed to record any further stones in the village, as well as carry out three drill cores to ascertain whether Nahariya had an ancient settlement history itself and thus whether there was any possibility that the blocks could have originated in the village.

Granite column being used as a corner preserver in Nahariya.

Three augers were carried out on the west, centre and east of the village. The first core to the west of the village beside the main canal, Tirat al Baguriyah, produced a faience fragment from a depth of 1.14 m and some Nile silt sherds above it, but the core was dominated by black silt to a depth of 5.5 m, suggesting again that the waterway was in an older water course.

Pigeon house beside drill auger.

The core in the village beside the main mosque showed that there was some kind of void between 2.2 and 5 m in depth, but that it had been built upon unsettled silt levee deposits. The blocks therefore probably did not originate here. In the third core to the east, an interesting settlement layer was noted from the ground surface to 4.5 m metres below the ground and that this was then founded upon alluvial silt. There seems to have been an older settlement here to the east of the canal, underlying this part of the village and, although the main mosque is clearly built upon the highest part its relationship to the eastern settled area is not yet clear.

Around 15 further uninscribed quartzite, granite, limestone and basalt blocks were noted in the village, mostly at the corners of the streets and also built into the steps of the mosque of Nur el Din Abu el Amaein.

Further work on a pottery collection would be useful to date the earliest settlement material at this village.

Hissat Birma N30º50.713’, E030º54.352’

Birma drill core area, south of one of the churches.

The town of Birma is first attested in texts in 1077 and in Hissat Birma, north of the old town there are two famous churches for St George. Three drill cores were carried out to the west, centre and east of Hissat Birma to begin to understand the sequence of settlement history at this town, a staging point on the way between Disuq and Tanta. The drill cores, perhaps indicated that there had been a waterway to the east of the town, leaving deposits of fine sand, alluvial foundations underneath the churches, and alluvial land on the east. There was no trace of earlier settlement in this area. Further work in Old Birma itself is necessary to understand why the town spread to the north and why the two churches were founded on apparently new land.

Birma is most famous for an appearance of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 2000. When we began work here, however, it was not the BVM who appeared but a landowner, who threw us off his land. We hopped over the wall and continued working on a footpath beside his land. By the end of the work we were all friends and he even provided tea.