Saïs Survey Report, 1997

Season Reports

Saïs Survey Report, 1997

Between September 21st and October 10th 1997 the EES Mission to Sa el Hagar (Sais) carried out a topographical survey of the area in the vicinity of the village of Sa el Hagar. The team consisted of Dr Penny Wilson and James Wright (1) and the work was facilitated by the kind help and co-operation of the Tanta Inspectorate of the Supreme Council of Antiquities and in particular Mr Said Hegazy, Dr Sabri Hasnin and Mr Ahmed Rashwan.

The survey concentrated on two main areas of the site:

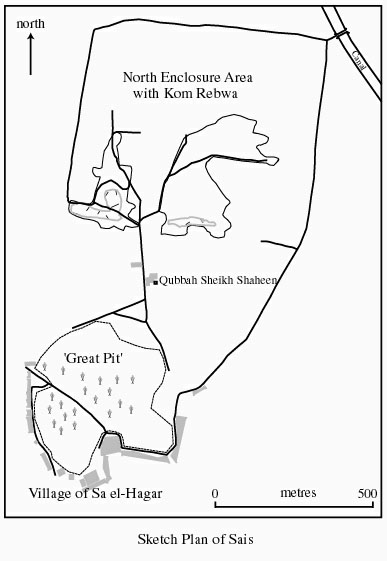

a) An area directly to the north of the modern village, which is now an extensive pit about 400m by 500m in area, called by the survey team ‘the Great Pit’. There are a few visible features here including a Hellenistic bath house excavated by the EAO in 1974,(2) a group of large granite blocks, some mud brick buildings, a limestone wall and a limestone covered drain or waterway. In addition there are areas of stratified dense pottery concentrations (Roman) and of smashed limestone and other stone chippings. A granite sarcophagus (removed in 1999 to the safety of the SCA Office at the site) and statue torso lying in this area were also recorded. At the east side of the pit, surface traces of building walls were noted and an attempt was made to mark them out for the topographical survey.

The exact nature of this ‘pit’ is unknown but it attests to extensive digging in the area over the past two hundred years or so. Some of the material may have been taken for sebakh to fertilise the fields, whereas other mud and soil has been removed to build the huge embankments along the Nile to the west, presumably to act as flood barriers in the years before the building of the Aswan dams. The questions of artificial flood barriers and whether the position of the ancient town of Sais moved during the course of her history has important implications for future work at the site.

The village itself stands upon a low but distinct mound and though the modern village is rapidly expanding, it should be possible to try to trace the extent of the ancient village in future work.

b) An area further to the north, known as Kom Farrays in some of the literature (3), but as Kom Rebwa on the local cadastral maps. This seems to be the area recorded by travellers to Sa el Hagar in the 18th and 19th centuries and drawn by Georges Foucart in 1894.(4) At that time a huge enclosure wall still surrounded substantial mud brick buildings. In separate visits, Wilkinson and Champollion noted that what was possibly the main temple here occupied the southern half of the enclosure and was orientated on an east-west axis.(5)

The enclosure wall has become the main track around the area, providing a solid and stable unmetalled road. It is about 10 metres wide at its widest point , but future work should be able to establish the true width of the enclosure wall, perhaps up to 28 metres wide.(6) The track encloses an area of approximately 750m by 675m, which must be the last vestige of collapsed and removed mud brick. Much of the area is under cultivated fields, but the extent of the areas recorded by Foucart and containing mud brick buildings and pottery mounds are still about the same. This non-agricultural land is officially Antiquities Department land and a few uninscribed large granite blocks lie hidden in the long grass. There has been considerable disturbance here and removal of sebakh on a huge scale, but we made a more detailed contour survey which may show areas from which mud brick had been removed. The negative spaces may be the location of ancient walls and some of the deepest diggings are now filled with water creating small lakes whose reed beds are the habitats of a wide variety of birds, small mammals and reptiles.

Patches of bare ground expose shattered fragments of all kinds of non-local monumental rocks including red and black granite, quartzite, limestone, sandstone and volcanic tufa. Foucart also noted a spring in the eastern side of the ‘enclosure’ which still exists and we noted. Wilkinson had suggested that the Sacred Lake of the Temple lay in the northern half of the enclosure and it could have been fed by natural springs such as the one here and in other areas of the site. In addition Foucart marked a sycomore-fig tree almost in the centre of the enclosed area and it seems that a descendant of the sycomore tree still grows here.

The topographical plan of the survey joins the two areas together for the first time in a detailed drawing (fig. 1) and further associated the areas with field boundary markers and the tombs of local sheikhs.

The survey also recorded standing monuments on the site and inscribed blocks and architectural elements at the Antiquities Office, including a fine colossal royal head, perhaps dating to Dynasty XXVI (7) and a block mentioning the particular form of Osiris at the site, Osiris Hemag.(8) Roman pottery from the Bath House area was recorded and the local inspectors took the team to a nearby hamlet called Kawadi whence part of a sarcophagus recorded by J-F Champollion in 1828 had recently been removed to the Antiquities office.

As part of a wider survey of the whole area the survey team cycled around the immediate area, to gain an impression of the access to the Nile and the flood embankment running alongside the river. In addition, we visited Rosetta and located in the Qaitbey Fort some of the blocks Habachi believed had originally come from Sais. (9) A visit was also made to Buto as a suitable comparison to the ancient city of Sais.

Notes

- I would like to thank Jim Wright for loaning equipment for the EES work and for giving his expertise so generously.

- J. Leclant, Orientalia, 44 (1975), 201.

- D. Arnold, Die Tempel Ägyptens (2nd edition; Augsburg, 1996), 218.

- G. Foucart, Notes prises dans le Delta, Recueil de Travaux, 20, 1898, 162-169.

- G. Wilkinson, Modern Egypt and Thebes (London, 1843, I), 327-328; J-F. Champollion, in Hartlében ed., Lettres et journaux, II (Paris, 1909), 98-105.

- As suggested by the plan of C.R. Lepsius, Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, I, pl.55-56.

- Found in June 1964 in the north east corner of the ‘Great Pit’, height 146cm, maximum width 109 cm F.M. Wasif, Soundings on the Borders of Ancient Sais, Oriens Antiquus, 13, (1974), 327-8.

- On this aspect of Osiris see now M. Zecchi, A Study of the Egyptian God Osiris Hemag (Imola, 1996)

- L. Habachi, Saïs and its Monuments, ASAE 42 (1943), 369-407.